Kaizen in Everything. But Why?

“The only true test of intelligence is if you get what you want out of life.” – Naval Ravikant

Ok, first let me get started by addressing the title of this article. Yes, I know that it’s impossible to quantify and compare the value of on-field and weight-room work. Yes, I have baited you into reading this article with a controversial title, but please let me explain why I’ve made this irrationally, oversimplified statement.

There are many reasons why I believe that the work done by a Strength & Conditioning coach on-field, is just as important as the work that they do in the gym. Note that I have said just as important, and not more important. Apologies for the click-bait (Sorry, not sorry). I’m going to split this argument into three parts in this article. Each one will hopefully make you think more about what the role of the S&C coach is, and how they can be better used by the athlete and the coaching team.

On-pitch S&C has been the most-neglected facet of the job for decades. In years gone by, the S&C coach was seen as the gatekeeper of the gym, and nothing more. “Teach my athletes to lift, and make them stronger”, was the only request made by the sport coach. Early in my career, I too was guilty of this belief, but I think that a lot of this stems from a culture and education system that deeply needs changing.

In the university classroom, we always spoke about sets and reps, exercises vs other exercises, rehabilitation and recovery. We very rarely, if ever, spoke about how you cue an athlete to run faster, change direction more quickly or dominate another athlete physically. So when I entered the profession, I saw my role as within the confines of the four walls of the weight-room. Then, when asked by my superior to take athletes through a speed session, I absolutely shat my togs. “How the hell do I do that?”. His head must’ve been wrecked by the sheer quantity of questions I threw at him, as I sought validation for my theories and potential methods. Nothing I had done up to this point, had prepared me for this. A clear failure of the current education system.

Now over time, I have developed my knowledge and coaching skills in this regard, but mainly by my own intensive learning. If we want to change this system and view of the profession, then we have to be the ones to do it. Wholesale change is required in terms of our own practice, if we are to permeate the minds of those outside the industry.

This poor understanding of how to coach skills comes from a poor understanding of how to reverse engineer sporting demands. Only once during my undergraduate degree, was I asked to identify the movements in a sport, and apply exercises in the gym that reciprocate and compliment those movements. Doing this for just one sport, that was assigned by my lecturer, was hardly enough to become competent.

A follow-on issue, related to this one, is that many S&C coaches are assigned to work with athletes from a sport that they know little about. Now, this may not be a problem from the outset, but to be a good S&C coach for a specific sport, you must know the sport inside out. You must know and understand, not just the physical demands of the sport, but also the technical, tactical and psychological elements, that pertain to elite performance. After you have identified, what this particular athlete does well, and does not do well, you should consult the sport coach regarding the type of “game” that the athlete is going to play. What is it that is going to set them apart from the opposition? And what is going to prevent them from doing so? Study, experiment, understand and apply.

As I outlined earlier, when first faced with the proposition of coaching speed and agility, I didn’t know where to start. Likewise when asked to coach body positioning and contact skills I was similarly lost. This stemmed from a belief that I had held, as a result of my education and training, but ultimately it was up to me to change my own perspective through research, trial and error.

The role of the S&C coach is not to teach you how to squat, bench and deadlift. Sure, that’s part of the job, but only a very small part. The role of the S&C coach is to guide an athlete to achieve a desired movement outcome. Now this can apply to benching heavier weight yes, but it can also be applied to running faster sprints, dominating in the contact-area or perceiving and responding to a stimulus more quickly.

Unfortunately, this is only skimmed over in traditional education as well. “This is how we test for this, this is how we test for that, etc”. Only by our own continual education and experimentation, can we learn how to make our athletes more effective in competition. So coaches cannot be reluctant to go beyond the scope of what they know. If you want to remain a weight-room coach, then by all means do so, but I believe you are doing your athletes and the profession a disservice by doing so. Go out into the field and learn. It may be outside your comfort zone, but that’s the only place that you will grow.

Teaching an athlete how to squat and bench is great, but let’s be honest, it has a fairly minimal effect over their performance in competition. However, if you make your athlete better able to evade their opponent, or knock them on their ass, then that’s going to go a long way towards helping them to win the game.

Acute injuries are often freak accidents, yes, but spikes in load are also to blame for athletes becoming more susceptible to such cruel twists of fate. Chronic injuries are equally a scourge on athletic development and performance, and can rarely be completely addressed from the weight-room. Injuries rarely, if ever, occur during lifting sessions. That is at least if you have a decent S&C coach overseeing everything. It is their job to prevent the athletes from themselves at times. “The best ability is availability” and you can’t be available for selection if you’re injured.

Typically, the training load on-pitch is more of a contributor to fatigue than that of the controlled environment of the gym. By having a S&C coach on-pitch to record and advise in terms of both training volume and intensity, the athletes can be better protected against injury. Thus the best team can stay on the field, available for selection by the head coach.

By monitoring volume and intensity, the athletes can also be aided in “peaking” for various points across the season. Using metrics to identify when to push the envelope and when to back off, can be a little beyond the scope of some head coaches. Occasionally, they will see no problem in a blowout in the immediate run-up to an important game because “That’s the way we did it when I played”. By picking the points where we are going to overreach and where we are going to allow more time for recovery, we can manage the athletes to reach levels of performance that exceed those that they have in the past. So maybe head coaches need to reassess, whether they need to have their S&C coach cooped up in the gym during the training week.

Who better to run “Conditioning” sessions than the very person who has it in their job title? As I outlined in last week’s post, conditioning sessions are often butchered by sport coaches, who don’t quite understand the energy system development that is necessary for high-performance in their sport. In order to run an effective conditioning session, intensity and volume must be carefully manipulated, by focusing on working times, volumes and rest periods. If the sport coach is secure enough in their own skin to hand over this element of training to the S&C, then he’s going to be blessed with fitter, healthier and better performing athletes. Not to mention, the athletes will thank him as they will be run into the ground no more.

So there you have it, in order to progress as a profession, responsibility lies with the practitioners to become better prepared for on-field work, the education system to modernise and become more practical in its nature, and sport coaches to become less insecure when handing over care to the S&C.

“The only true test of intelligence is if you get what you want out of life.” – Naval Ravikant

So, we can see that when it comes to our training, a certain volume of work when paired with adequate recovery is positive for our development, but if that same intensity of work is mismanaged and spiked, then the same exercise intensity can be toxic to the athlete.

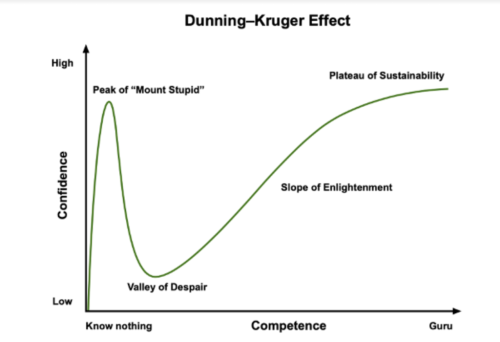

Unfortunately, it takes a fall from the peak of mount stupid, on top of the Dunning-Kruger curve, for many of these lessons to land home.

Here to help you achieve your health and performance goals.

At Petey Performance, I’ll assist you every step of the way. What’s stopping you?

Take ownership today.

© 2021 All Rights Reserved

Subscribe to Petey Performance and get updates on new posts plus more exlusive content.