Kaizen in Everything. But Why?

“The only true test of intelligence is if you get what you want out of life.” – Naval Ravikant

Pre-season is just around the corner.

We’re well into the off-season now. There’s very little time left to get some work done that’ll give you a head start on your opposition come January.

And if I said to you that I could give you that head start, with minimal training time and commitment involved, then you’d likely bite my hand off.

Pre-season is often seen as the time that we “get back to full fitness”, with a large amount of training time dedicated to developing the physical aspects of the sport. And I’m not here to say that that shouldn’t be the case. However, what I am here to say is that it’ll be a lot easier to get ready for that first throw-in, if we stay as ready as we possibly can for it.

As I’ve spoken about on previous blogs, over the course of the season, there are many aspects of the sports of gaelic games that we must focus on developing. Time will need to be given to developing the athletes in both a technical and tactical sense, as well as more time honing psychological skills. And any time given to these aspects, no matter how essential, will detract from time given to physical development.

Unfortunately, the games we play are not simple ones, with many components adding up together to make the complete player. And we absolutely can’t spend the majority of our time focused on improving physical metrics and qualities. And nor should we want to!

So then, if we are to identify when the best time to develop physical aspects of a players game is, it is most certainly when there are absolutely no requirements in terms of teaching and learning a tactical gameplan, as well as less of an emphasis being placed on honing technical skills. This is our opportunity to be more aggressive in our approach to developing physical qualities, and it is undoubtedly the best opportunity we have to develop the “athlete” in this regard.

We may call these periods of time “developmental zones”, as we are provided the opportunity as performance staff to really push our players to improve their athleticism. So, if this is the best time for players to improve their physique, strength, power, speed and durability, then it must also be the best opportunity we have to improve their conditioning as well.

Players usually see pre-season as the time that they get back to match-fitness. Some of them may even say that they don’t get back to the same level of “match-sharpness” until they’ve played a couple of games. And whilst they may be correct in some regard, we are likely leaving potential gains in performance on the table if we solely rely on match-play and small-sided games to develop match fitness.

Now I’m not here to bash a games-based approach. In fact, I believe that there is more to be gained by that kind of approach to training than others. However, what I will say is, just because it prepares us to execute skills and make decisions at both high-speed and under fatigue, doesn’t mean that it takes care of training every aspect of the game.

As outlined previously, if we are to improve in relation to our performance at any given sport, we must first “reverse-engineer” the sport. That is, break it down into its component parts, train each of those, before integrating them together and building athletes back up to a higher level of performance.

If we are to look at the aspects of “conditioning” that affect performance in the game, we may see that athletes must be conditioned to make many decisions with a high level of success. They must be conditioned to sprint maximally over moderate distances repeatedly. They must be conditioned to decelerate and change direction over and over again in response to what’s happening on the field. And their limbs must be conditioned to tolerate all of these demands, as well as the demands of jumping, landing and physical contact, over the course of a game.

I’ve already gone through my approach to developing qualities of speed, change of direction and decision-making in my first article of this series. So, if we park that, and focus on some of the other aspects of the sports of gaelic games, we may see that what I haven’t yet covered is aspects of improving “tissue tolerance” and improving the athletes ability to execute powerful movements, such as jumping and tackling.

I’m going to save my approach to developing power and jump ability for article 4 of this Off-Season series. So keep your eyes peeled for that one. But for now, I’m going to guide you through my process for improving tissue tolerance and conditioning on the field of play.

This may also have the desired effect of improving an athlete’s ability to tolerate both match-play and training, which will in turn reduce their risk of injury. And we all know that in any sport, the best ability is availability! It may also explain why I don’t ever prescribe road-running to my hurlers or footballers. This is just my personal preference and hopefully after outlining my rationale behind it, you’ll have a better idea of why I think about training the way I do.

In relation to off-season training, something that most coaches get right is prescribing some aerobic running or conditioning. If we are to recover quickly in between bouts of high intensity, such as sprints, then we must have an efficient aerobic system. Often athletes take the opportunity of the off-season to look to develop their aerobic performance. After all, it’s one of the only opportunities they will get where they have the time to focus on doing so.

Whilst a general approach to aerobic system development is most certainly beneficial, it has been shown that we can only influence our VO2max (the gold standard measure for aerobic fitness), by 15-20% on average through training. It has also been shown that well-trained individuals can have less of an impact on improving their VO2max. So, whilst long duration steady state running or off-feet training may be extremely beneficial for those athletes who are poorly trained in relation to their aerobic fitness, it may have diminishing returns on athletes of a higher level or greater training age.

I don’t know about your specific situation, but I would suggest that most senior club players that I work with, would be considered to be highly aerobically fit in comparison to athletes in other sports I’ve worked in. Does that mean that I don’t train the aerobic system?

Absolutely not.

But what it does mean is that when we complete our training in relation to aerobic development, I typically prescribe movements and intensities that are more appropriate to the games of hurling and football.

What movement do we perform most often during a GAA game? Running of course.

But, when we are running in a game, do we run continuously? Definitely not. And do we consistently plod along throughout the game at low intensity? Definitely not.

So then, what do we do? Well we sprint, change direction and jump at high intensities, which I’ve already covered. And which will all be covered in other aspects of our training. So, with all of those bases covered, then what other intensities are we not covering. It’s obvious to me that we’re not covering running at submaximal intensities to a sprint. So, not quite a sprint, but not quite a jog either. This occurs more times than you can imagine over the course of a game.

So, if we look at the SAID principle (Specific Adaptation to imposed Demands), then we understand that the body adapts to the demands placed on it. So, why then would we neglect to train the aspect of the game that occurs very often and is extremely fatiguing to the player in question? This is why I often prescribe tempo running to my athletes during developmental zones.

When we perform tempo running, we are simultaneously training the aerobic system, whilst conditioning the lower limbs to tolerate intensities and movement velocities that are most common during a game of football. I never think about conditioning solely in relation to the aerobic system. I always consider the “conditioning” of the muscles to tolerate movements that occur in game. If we can tolerate those movements, then they’ll be less fatiguing and thus we will be able to recover from them quite quickly and as a result our injury risk will be lower.

If you’re planning on going out and implementing some tempo running into your training, the best advice I can give you is to make sure you’re running slow enough, but with quality running technique. In order to maintain this technique over time, you’ll have to maintain your level of intensity. Often I see GAA athletes take off like a shot on their 1st run, only to be left heaving in the ditch by the last one. Needless to say the quality of these efforts is significantly different, and therefore the loads going through the lower limbs are also significantly different. Always aim for running at 70% of your maximal sprinting speed.

Below is a sample tempo running session that I would prescribe, and if looking to develop the aerobic system, I would always aim for equal work:rest ratios. That means if the run takes 15s, then the rest period will be at least 15s.

As you become more proficient in running at these velocities, you should progress your distance or running volume every week. If you get to a stage where this becomes too easy for you, then I would suggest getting creative and implementing some COD movements at submaximal intensities into each tempo run. But remember, if that work:rest ratio becomes significantly altered (Work>Rest), then it’s likely that movement quality will suffer and as a result you will likely be entering more anaerobic heart rates and training zones.

In my view, Quality > Quantity always.

If you’re doing 2 tempo running sessions on a weekly basis, and still feeling that you need more exposure to aerobic training to improve, then I would suggest implementing some off-feet aerobic training into your program. Sure, it may not necessarily be specific, but you’ve already got enough specific work in your program to cover your bases of tissue tolerance and honing movement technique. Any extra would likely just decrease the quality and increase your risk of injury due to fatigue.

So, if you believe you need to improve your aerobic conditioning this off-season, it may only take a couple of nights of dedication. Don’t let time slip by without taking advantage of it. Get to the pitch and get after it. And if you can’t get to the pitch. Then something is always better than nothing. Just because something’s not the best thing, doesn’t mean it’s not beneficial.

“The only true test of intelligence is if you get what you want out of life.” – Naval Ravikant

So, we can see that when it comes to our training, a certain volume of work when paired with adequate recovery is positive for our development, but if that same intensity of work is mismanaged and spiked, then the same exercise intensity can be toxic to the athlete.

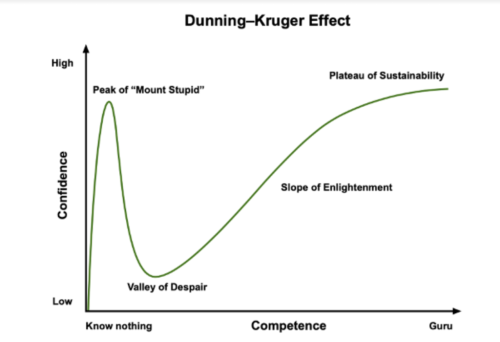

Unfortunately, it takes a fall from the peak of mount stupid, on top of the Dunning-Kruger curve, for many of these lessons to land home.

Here to help you achieve your health and performance goals.

At Petey Performance, I’ll assist you every step of the way. What’s stopping you?

Take ownership today.

© 2021 All Rights Reserved

Subscribe to Petey Performance and get updates on new posts plus more exlusive content.