Kaizen in Everything. But Why?

“The only true test of intelligence is if you get what you want out of life.” – Naval Ravikant

It can be hard to go against the grain. When you’re in the storm, it can be very hard to see your hand in front of your face. However, if you’re to be one of those magnificent people that succeed far above expectations, you’ve got to get to the eye of the storm, survey the lay of the land and see something that others do not. You’ve got to be an innovator. At least you’ve got to do your best to be one.

Now, that’s not to say that absolutely everything you do has to be completely outside the norm. Innovation doesn’t mean throwing out absolutely everything that has come before you. It probably means doing what has been done to this point to an extremely high level, but adding something slightly different to your process as well. This add-on is something that takes what you’ve already perfected, flips it on its head and makes it work even better.

I often talk about how coming to work in the GAA, from a rugby background, with a huge interest in many other sports, has given me a distinct advantage in seeing how things are done and asking whether there may be a better way to do them. I’ve never been completely boxed in and constrained by the customs and culture of the sport.

When I was told that we simply couldn’t perform our pitch and gym sessions on the same day, I laughed and said we’d give it a go.

When I was told that I couldn’t train GAA players like sprinters, that they wouldn’t be able to tolerate sprinting distances greater than 50m, I also laughed and said “well let’s try it and see what happens.”

Two years later, our players are all hitting higher max speeds than they have done previously, they’re covering more high speed running distance in games and sessions, they feel more fresh in those sessions and their buy-in to the S&C program has been as a whole, way, way better.

We’ve also seen a reduction in the incidence of acute injuries and self-reporting of feeling “better able to get around the field”. We absolutely can’t claim that the implementation of such outside of the box ideas is the cause behind the effect, but it definitely hasn’t impacted the changes negatively.

As I continue to develop and hone my understanding of the games day by day, I continue to question why we do things a certain way and what we can learn from other sports that we then can implement into our own.

As my role has progressed from an overview of the S&C program, to that of head of the whole performance program, I’ve had to attempt to understand the various drills, games, tactics and learning objectives that our coaching team have sought to implement.

One of my strengths over the past couple of years has been my ability to see associations between two very different things. Sometimes I wonder if they’re very different at all.

As I sat in team meetings, listening to the tactical coaches speak about spacings, closing space, creating space and converting opportunities, I couldn’t help but remember the many times we would have those very same conversations amongst the rugby and soccer teams I was a part of as a player. Sure, the terminology was slightly different at times. Double-ups vs two-on-one tackles, showing the touchline vs using the touchline as another defender and pressing vs rushing! However, the ideas behind all of these team-sports are the exact same. Own possession, own the territory battle, create the space, find the space, convert the chances and put the opposition under pressure.

When developing my gamespeed model for GAA, I took into account the many different scenarios that players may find themselves in on the field. I adapted my back catalogue of rugby coaching, evasion and decision-making drills to those very scenarios, and saw my athletes absolutely see the transfer of those drills to the field of play. I realised that many of my drills were focused on attack, with very little time given to how to coach our backs on how to close an attackers space and make it as difficult as possible for him to get a shot off. This took me to a place where I had to make an effort to watch and understand how to defend effectively in Gaelic football.

Following conversations and observation, I realised that there were similar principles at play in GAA as there are for defending in soccer and rugby as well.

This led me to reach out to coaches working in both rugby and soccer, to learn more about how to coach transitional movements and spatial awareness on the field of play.

I tried many, many drills. Some were great and I held onto them, fitting them somewhere into my process. Some were not and I either threw them out or adapted them to make them better. Only through trial and error though could we seek to discover something that the opposition had not. Only through doing things a different way, could we innovate and train the qualities that were so often simply left to the players to “figure out themselves.”

We’ve spoken about structuring the week and the training differently, as a result of using principles of play from rugby and association football. What came next was a restructuring of how we planned and periodised our training program throughout the year to maximise the gains we could attain in the realms of speed, power and conditioning. All whilst minimising injury risk.

For this I borrowed principles of track and field from great coaches like Charlie Francis, Dan Pfaff and Frans Bosch. Implementing a speed-based program, focused on developing the ability of the athletes to sprint and accelerate maximally with mechanics very like elite-level sprinters. We used a High-Low model to approach our weekly and monthly schedules, getting the most out of our “High” days, as well as our “Low” ones too.

The idea for colour-coding these sessions may have been borrowed from Fergus Connolly, but the “Feed The Cats” mentality of training how we want to play was definitely taken from Tony Holler’s approach to track and field.

I’m not saying that our model is perfect. No models are. All models are inherently wrong, but some are useful. And we’ve found this one to be useful.

Which brings me to what is peaking my interest now. The tactics of the games.

As you can probably tell I’m an avid sports fan and enjoy watching games of just about any code. One of my favourite things to do when watching these games is to attempt to understand what’s going on on the field. What are the tactical approaches of both teams, how do they seek to make the most out of their strengths and where does it leave them vulnerable? I love watching the game of human chess play out in front of me and often find myself attempting to predict what is going to happen next. Maybe this comes from my days playing rugby as a 9, 10 and 15, where you really have to have a sixth sense for what the opposition are trying to do.

So, as I watch soccer at the moment and see the revolution of stats, tactics and expected goals, I can’t help but seek to understand whether a similar approach may work for so-called “underdogs” in GAA. Can the Louth’s and Leitrim’s of the country attempt to get a jump on the gargantuans of Gaelic football through an innovative approach to their performance analysis and a fresh tactical approach.

We see gaelic football change all of the time, as a new team takes over with a certain setup or principle that leaves the opposition perplexed. We then see every team attempt to copy them in their own way as they try to get with the times and keep up.

So my question is, can the smaller counties learn something from Brighton and Hove Albion, Burnley and Brentford?

One such example that I’ve been toying with is whether the principles of attack and defence in soccer can be adapted and made use of in GAA.

Could Brighton’s innovative formation and use of static central defenders as playmakers transfer over into breaking down packed defences in Gaelic football? I for one would love to see a “risky” option used to entice blanket defences out of line as they sniff a turnover. Only by doing so can we seek to more easily create gaps to exploit in said defence.

Could Brentford’s quick transition, long-ball game be used by a county with less resources to great effect in their pursuit of Sam Maguire? One thing is for certain, the players that employ such a tactic will definitely have to be conditioned to do so.

What can we learn from the principle of selecting players based on their expected goals per game stat in GAA? Could we see a county start to pick more players from clubs plying their trade in the junior and intermediate club championships? Based purely on players effectiveness, likely scoring differential or net positive return in terms of their actions in match-play.

I don’t know if there’s something there, but I really feel as though the next great revolution in GAA will be one based on the use of statistics. I’m just excited to see who gets there first.

“The only true test of intelligence is if you get what you want out of life.” – Naval Ravikant

So, we can see that when it comes to our training, a certain volume of work when paired with adequate recovery is positive for our development, but if that same intensity of work is mismanaged and spiked, then the same exercise intensity can be toxic to the athlete.

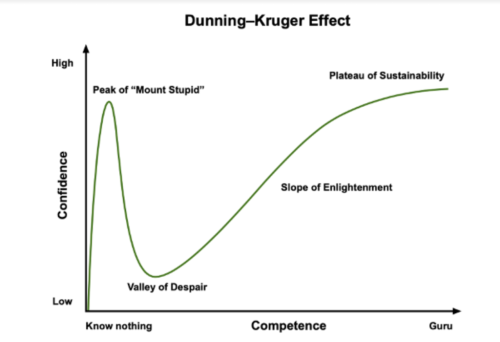

Unfortunately, it takes a fall from the peak of mount stupid, on top of the Dunning-Kruger curve, for many of these lessons to land home.

Here to help you achieve your health and performance goals.

At Petey Performance, I’ll assist you every step of the way. What’s stopping you?

Take ownership today.

© 2021 All Rights Reserved

Subscribe to Petey Performance and get updates on new posts plus more exlusive content.