Kaizen in Everything. But Why?

“The only true test of intelligence is if you get what you want out of life.” – Naval Ravikant

“The Dose Makes the Poison” is an old adage that explains the principle of toxicology. It has been used for the last 500 years, to convey that it is not the presence of a substance that causes illness or dysfunction, but the concentration of that substance.

Although it was initially used and still is used in a biochemical or biomedical sense, it can be used in just about any facet of life as well. The major example that comes to my own mind is obviously in relation to the physical therapy or rehab space. Here it can be used to explain why it is that some athletes suffer acute or chronic injury in response to a specific stimulus, whereas others tolerate it with no problems whatsoever.

If we understand that different athletes will have different levels of tolerance for different volumes of work at any specific intensity, then we can understand that the necessary volume of work to induce injury or rupture of a specific tissue, will be different for and specific to each individual athlete.

By understanding this, we can understand that if working with any team, we need to individualise our training program and exposures to each athlete, by training within a bandwidth, defined by averages, for their tolerance levels to specific exercise modalities or intensities. The goal will always be to enhance the tolerance level and capabilities of the group, but there is no point in pushing the ceiling of the top performers up, whilst losing those at the floor to injury. If you don’t have players available to play, then it really doesn’t matter how strong your best performers are, as the game is a team-game. The easiest way to guarantee failure is to not have enough players available to take the field.

So, working with teams on their physical performance is a precarious balancing act, where you have to understand where each athlete is in relation to their function and performance and be receptive to significant changes in training volumes and stress, so you don’t fill the cup up so much that it overflows.

We can always improve in any area, but it is a question of prioritisation whether each area needs to improve at any given point in time. If we chase increases in tolerance in every area of performance concurrently and continuously, we can’t be surprised if one or more areas of our athletes’ performance suffers or breaks at any point in time.

As human beings, we can only tolerate a specific amount of stress, a specific volume of work and achieve a specific amount of adaptation on a daily, weekly, monthly and annual basis. Training therefore is a balancing act between training and recovery, in which we must make the best use of our time and resources, to improve the athlete’s abilities in the shortest but also safest manner.

Sure, we can choose to be more conservative or more aggressive at different stages of the season, but if there isn’t any specific need to be aggressive, then the potential for missed sessions, weeks and months through injury, really isn’t worth the risk. It is better with fit and healthy athletes, to creep forward one step at a time, than it is to go two steps forward and one step back as a result of poor planning, aggressive loading and impatience. In my experience, playing the long game in terms of long term athletic development in a progressive and rational manner, is a whole lot easier when you don’t have to worry about an extensive list of previous injuries, resulting from such periods of mismanagement and impatience.

So, we can see that when it comes to our training, a certain volume of work when paired with adequate recovery is positive for our development, but if that same intensity of work is mismanaged and spiked, then the same exercise intensity can be toxic to the athlete.

So then, when we hear polarising opinions and methods for development that place a heavy emphasis on specific training modalities and/or physical qualities, we can appreciate that although these methods or systems can be beneficial for specific athletes who are underdeveloped in these areas, they likely won’t work forever. Once they’ve realised the potential of training in this manner and being exposed to this higher than usual volume of work (as long as it’s been progressed gradually), then any significant increase in exposure thereafter, is not likely to be of as much benefit to the athlete and as a result may come with some inherent additional risk.

This is particularly applicable in the rehab and return to play space, where a coach must take an athlete from a position of low tolerance and reduced volume of work, to a position where they are confident that the athlete will be able to tolerate multiple different movement demands, intensities and volumes, throughout the unpredictable experiences of training and competition.

The job of the rehab professional is then not as it used to be, where they would often simply deload the athlete and allow rest and manual therapy to reduce inflammation and reduce incidence of pain. But now they must pair that with, adding an acute dose of training regularly, to not just return the injured tissue and athlete back to the level they were previously at, but guide the athlete to a position where they are able to tolerate a greater dosage of that specific intensity and volume and complete it with greater success than previously.

If we get the athlete back to where they were, then the likelihood of them becoming re-injured when they experience that specific dosage again will be quite high. However, if we are confident that they can tolerate a greater dosage of that intensity prior to their return, then we will have greater confidence that they will not become re-injured should they experience that dosage again. We must define what dosage is necessary based on the movement demands of the sport and the athlete’s role for their team.

So, if we appreciate that team-sports require the athlete to move in multiple different ways, at multiple different intensities and for multiple different durations, then we should understand that we can’t go after improvement in just one area for the duration of our time working with them. We must be receptive to the athlete’s own individual adaptation and make judgments on when to attempt to induce adaptation of some physical qualities and when to choose to forgo training those qualities to go after others that are more important at this specific time. We then must keep enough exposure to those qualities, that we are not currently chasing, in the program, in order to maintain those qualities and not have them become detrained.

We can do this in two ways. We can either be completely receptive and reactive in the moment, making decisions day by day, or we can systemise our process, but appreciating the transitory nature of training and understand that any system needs to be adapted to meet the athlete where they are now. The latter allows for greater objectivity and perspective. It provides us with a framework for programming, it allows us to be confident that we are leaving no stone unturned and it allows us to use our experience for our athlete’s greater benefit in the long term. It also allows us to not become lost in the emotional process of rehab and allows us to be more future focused in our work with our athletes.

So, although you can have a framework or system for your training and rehab process, you also must be able to adapt that process to suit the athlete in front of you. You need to be receptive enough to understand where the athlete is in the present, but you must also be far enough removed that you are able to step back and observe the bigger picture of long-term development. You must understand what dosage is necessary at the moment, to prepare you for the dosage that is to come down the line. You must understand that the dose makes the poison, but be confident enough in your abilities as a coach to increase the dosage all the while.

“The only true test of intelligence is if you get what you want out of life.” – Naval Ravikant

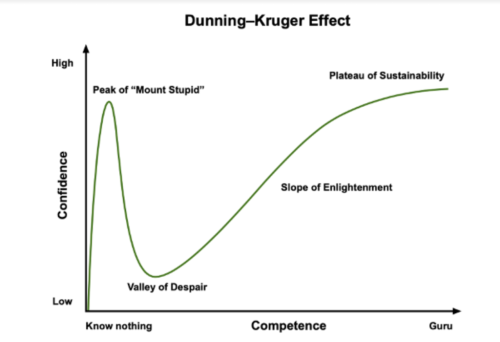

Unfortunately, it takes a fall from the peak of mount stupid, on top of the Dunning-Kruger curve, for many of these lessons to land home.

Pick your big rocks. These are the things that will really push you forward as an athlete at this stage of the process. Prioritise these above all else. These are the need-to-haves. Don’t ignore these in favour of the nice-to-haves.

Here to help you achieve your health and performance goals.

At Petey Performance, I’ll assist you every step of the way. What’s stopping you?

Take ownership today.

© 2021 All Rights Reserved

Subscribe to Petey Performance and get updates on new posts plus more exlusive content.