Kaizen in Everything. But Why?

“The only true test of intelligence is if you get what you want out of life.” – Naval Ravikant

Chances are you’ve heard the following excuses more than once. “Those boys would run all day”, “They were just way too strong and physical for us” and “They just wanted it more”. But very rarely will you ever hear, “They were just a more skilled and better-prepared side”. In the GAA, when the team loses, the finger is almost always pointed at the team’s conditioning or lack thereof. I heard an analogy of late that really hit home. Blaming the S&C coach for a team’s failures, is like being in a car crash and blaming the guy that was sitting in the back, keeping an eye on the cup-holders. Now this may be an extreme case and though it is primarily an attempt at humour, it does hold some truth.

Intercounty GAA’s level of performance and conditioning has increased exponentially in recent years, but still has a long way to go at a grassroots-level. For some reason, Ireland’s national sports have been more reluctant than others to do away with their old traditions and consider principles of sport science and strength & conditioning in their training. There are many factors that contribute to this, many of which have nothing to do with sport or science at all.

However, if you were to ask the head coach of any club-side around the country, if they used strength and conditioning techniques in their sessions, you would be almost guaranteed to receive an answer of yes, in response. Show their training program to a S&C coach and the professional in question will more than likely begin to feel either infuriated or nauseous. So clearly, there’s something being lost in translation here.

Now, I’m not here to say that all head coaches haven’t got a clue when it comes to physical training. No, most of them have a fair idea what it’s all about. However, what they are lacking is an understanding of the essential intricacies of sport science, and get mixed up with some of the terms that are used in the field. So what I aim to do with this article, is to dispel the bullshit and clean up the areas of uncertainty around terminology and best practice.

Intensity is defined as the amount of physical power generated when performing an activity. Volume is the amount of work done. It is by the very nature of the definitions of the two that it is quite difficult to have high amounts of both in a session. So, if you want high-intensity in your sessions, you should have a relatively low total volume, with fairly generous rest-periods. If you want to put your team through a high volume session, then their average intensity will be reduced, in order to complete the session. Human-beings only have a certain amount of energy stored in reserve, and when these reserves are depleted, the athlete will not be able to reach the same intensity as they did, when these reserves were full.

As the saying goes, “Any idiot can make another idiot tired”. That is not what coaching is about. Coaching high-performance is about “high-performance”. How do you measure a GAA team’s performance? By their ability to play the sport of course. So having them run themselves into the ground is probably doing more harm than good. Get them better at playing the sport at speed.

If you want to perform at high speed and high intensity, then you have to train at high speed and high intensity. Train like high speed is a habit that you’re trying to promote amongst your squad. Training at lower intensities is going to do sweet fuck all other than prolong the length of your sessions. Sometimes less is more, and GAA players are starting to figure this one out. Highly-esteemed physiologist Henk Kraijenhof once said, “Minimum effective dose is the aim of the game”, “Train as little as needed to develop and win, not as much as possible”. If I could get one thing through to the amateur coaches around the country, this would be it.

There is absolutely no need to complete four 90-minute sessions per week, as many teams do. This is absolute overkill. Train at speed, play at speed. Focus on the quality of the sessions, rather than the quantity. Come to a session well-prepared, with a clearly defined session plan, objectives and timings on paper. Get there, get it done, and get home for some much needed rest and recovery.

This one is tricky. Outside of the sport science industry, not many people have a clue what you’re talking about if you bring up energy systems. Sure they’ll be able to throw out some buzzwords, like “Lactic Acid” but they usually won’t understand how energy systems work, or how to train to stress and enhance a particular system’s performance. So I believe that the most beneficial thing to do here, is to put my money where my mouth is and attempt to explain in layman’s terms how each system works, how it pertains to GAA performance and how to train to stress the particular system.

Before we begin, for those of you that are completely lost already, energy systems can be defined as the ways by which the body produces fuel for our working muscles during activity. There are three (debatable) primary systems, all of which will be relevant to the sports of GAA, but each are of primary concern for different, specific tasks relating to the game.

This system is the first used in order to produce the required energy to execute a physical task. It usually pertains to powerful muscular actions, which is why it is of particular importance for GAA players, especially goalkeepers. It is primarily used for short, intense actions such as sprinting, jumping and tackling. This system is quick to produce energy but also extremely quick to fatigue, which means that we are unable to sustain activities for more than a few (~10) seconds when required to use it.

As an example, imagine when a goalkeeper is forced to make a couple of successive saves, or an outfield player is forced to perform a couple of maximal effort sprints in quick succession. Following that, that player is going to feel fairly depleted of energy, regardless of their fitness level, and if required to perform another powerful action immediately following that, their power output is not going to be what it was before.

This system can be trained in the gym or on the field, but in order to train this system, long-duration rest periods are required. This does not mean 60s rest, as many coaches see as plenty of time for full recovery. No less than 2-3 minutes are required for almost full recovery of the system, but the system will not be fully replenished if the demands of the task exceed the length of time that the system can sustain energy.

This is the one that is primarily worked on by GAA coaches up and down the country. Anaerobic basically means without the presence of oxygen, and that is why you’ll feel as though your lungs are completely devoid of oxygen after using this system excessively. The system is not as powerful as the ATP-PCr system but it can sustain exercise for 30-90s before energy production starts to decrease, and the athlete begins to become fatigued.

This system is important for medium intensity activities, which are a part of GAA, but not the determining factor in answering the question of who is the better-conditioned side. So when athletes are asked to complete run after run, shuttle after shuttle, the athlete’s movements begin to decrease in power output and become more laborious, as they attempt to sustain repetitive efforts.

If you train continually using this system, as many coaches do, it will make your athletes tired, but as outlined already, the goal of the coach is not to simply induce fatigue. Simply training an athlete to fatigue doesn’t train the energy system to improve. If it were that easy, the team that does the most fitness work would win the championship every season, and we all know that this is not the case.

However, this is not to say that we should never attempt to train the Anaerobic Energy System. There is benefit to training at High, Medium and Low intensity at various times throughout the season. However, at the moment, it seems as though medium intensity work is favored by most coaches, and my point is, that type of training is very specific and will only take us so far.

If we are to train this system optimally, I would suggest that we identify when we are attempting to train this system, and provide sufficient rest, so that movements don’t become laborious or exaggerated.

We also need to factor this volume into our weekly load monitoring. If we have a high volume of moderate intensity work, combined with high intensity work, during every session in the week, we’re actually asking for any injuries that come our way. Some high days, some low days, some moderate days is most likely the way forward.

If you don’t have a GPS to track volumes and intensities, as the vast majority won’t, just make an attempt at estimating distance covered by looking at the length of your drills/games and amount of efforts players perform. Then classify the day as either high, low or moderate, and factor it into your week. Ideally, I tend to go with a high-low model of 2 high volume days and 2 low. As a general rule, try not to have more than 2 high days, and at least 1 low day in a week of training.

This is the energy system that uses oxygen to help with energy production. Many people would consider this system to be the long-duration system, and to an extent they can be considered to be correct. The aerobic system is heavily engaged in low-to-moderate intensity activities. However, it cannot be neglected, even within team-sport athletes, as it plays a crucial role in recovery and many of the actions over the course of a hurling or football match are at that very intensity. Up to 60-70% of distance covered during a football or hurling match are at low-to-moderate speeds (<4.8m/s)

The aerobic system is always contributing to energy production, but the degree to which it does so increases with duration. After 90-180s, the aerobic system will be contributing the most to energy production. So it is crucial that all GAA players have a decent level of aerobic conditioning. However, in my experience, most already do, which would suggest that giving all of your athletes additional low-moderate intensity running (5-10km), is doing very little other than wasting time that could be better spent in other areas. Not to mention, adding to an already high volume of lower limb impacts throughout the week. I need only use the amount of athletes that have come to me with various tendinopathies and shin splints this past year, as evidence that running volumes are a tad excessive throughout the country.

This system also gets a lot of work in the traditional training model for GAA. How many times have you heard, “No rest, go again!”, shouted at you from the sideline? However, there are much better ways to train this system, than simply providing insufficient rest periods.

If we are going to attempt to stress this system using a games-based approach, we want to widen space so that players must cover more ground. If we want to improve aerobic conditioning on-field in a more controlled approach, then extensive tempo running is the way to do it, in my opinion. We can have a whole group of athletes simultaneously running position-catered distances at a relatively high intensity, which allows them to focus on sprint-mechanics without becoming fatigued.

If we have a player that needs particular work in terms of aerobic conditioning, then they can be given top-ups in terms of tempo running throughout the week. However, if their total running volume is already quite high, it may be best to perform additional aerobic work off-feet, on the bike, ski erg or rower, in the gym.

The old cliche is true. “Speed kills”. Our level of playing-ability in a sport, is largely based on how fast we can perform the movements relevant to that sport. Those movements could be sprinting, changing direction, jumping, tackling, shooting or passing. The faster player usually wins the moment, and as we all know, winning a game is all about winning more moments than the opposition.

If we are to win more moments than the opposition throughout the course of the game, we have to be slow to fatigue, so we have more energy for subsequent moments, enhancing our ability to exert ourselves. If we are efficient at performing the relevant skills/movements throughout the course of the game, then we are going to waste less energy, and have more energy in reserve. This is why, the team that covers the most ground, often does not win the game. The players of the victorious side are consistently in the right place at the right time, before the opposition. They execute the skills/movements better than the opposition, winning more moments and thus winning the game.

So then, should at least some, if not most, of our focus be on improving the speed and efficiency of our movement in our training? Often teams will set aside time to do this in relation to striking or shooting, but how often do they set aside time to work on sprinting, running, changing direction and winning the contact area? Now I’m not saying that we have to leave the hurleys or the balls to the side and start training our athletes like they’re in the NFL combine. What I am saying is it may be useful to set aside some time during the session to educate our athletes on how they can sprint better, how they can change direction more quickly and how they can manipulate their opponents bodyweight in the contact.

From my experience, the best time to do this is in the warm-up. The athletes are fresher, so movement execution and efficiency is at a maximum. It sets the tone for the oncoming session and allows athletes to mentally switch on for the session ahead. Most importantly, it is the time in the session that the head coach or trainer is least territorial over. If we manage to negotiate 10-15 mins prior to each session in a week, and we have 4 sessions, we’ll get in almost an hour of additional movement focused S&C work. Break that up over a 6 month season, and it’s almost 24 hours of S&C work on skills that have a direct impact on our ability to play the game.

Now as we said, we may not always be so lucky to get a full 15 mins prior to each session to work on these skills. So then just look for enough time to get a small bit done during the warm-up, and ask for shorter 1-2 minute blocks in between drills and games. Use it as “Conditioning” and if you get 2-3 of those in during a session then you’re laughing.

I truly believe that we are beginning to see significant change in the landscape of GAA S&C. However, whilst county teams all over the island are beginning to hand over care of their athletes to Sports Medicine teams, I fear that the gap may widen between inter-county and club-level athletes. Already we are seeing Dublin GAA take leaps and bounds ahead of other counties in terms of S&C, and if the barriers towards progression outside of the capital are not addressed, their reign may continue as the annual winners of the championship.

The good news is that players are beginning to take ownership and stand-up for themselves as they realize sometimes “less is more”. A lot of this can be put down to the amount of good quality online content being put out there by diligent S&C coaches. Players are now demanding that their clubs invest in the areas that have a direct impact over their performance, as they go against the ever-present hierarchy within those same clubs.

However, until the old heads can renounce their egos and appreciate that someone may know better than them in certain areas, we will always come up against a good deal of resistance when driving player-centred scientific-based care. The onus is also on the S&C coaches though. We have to make a conscious effort to develop trust between the traditionalists of the board and ourselves. When both of those things occur, who knows what levels of athleticism we will behold on grass-pitches around the country.

Thanks to Joel Jamieson, Dr. Yuri Verkhoshanksy and Dr. Fergus Connolly, along with the Strength Coach Network, for the information and inspiration.

“The only true test of intelligence is if you get what you want out of life.” – Naval Ravikant

So, we can see that when it comes to our training, a certain volume of work when paired with adequate recovery is positive for our development, but if that same intensity of work is mismanaged and spiked, then the same exercise intensity can be toxic to the athlete.

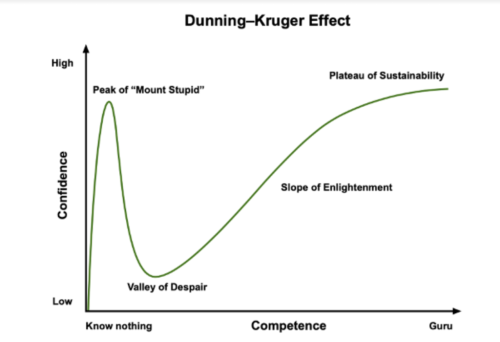

Unfortunately, it takes a fall from the peak of mount stupid, on top of the Dunning-Kruger curve, for many of these lessons to land home.

Here to help you achieve your health and performance goals.

At Petey Performance, I’ll assist you every step of the way. What’s stopping you?

Take ownership today.

© 2021 All Rights Reserved

Subscribe to Petey Performance and get updates on new posts plus more exlusive content.