Kaizen in Everything. But Why?

“The only true test of intelligence is if you get what you want out of life.” – Naval Ravikant

Strength & Conditioning social media will be bombarded with posts on Return to Play (RTP) for GAA in the coming weeks. Though these accounts are right to forewarn the pitfalls of a hasty return to performance, many of them don’t actually inform a whole pile in terms of their actual RTP protocol. As they outline the importance of RTP for the individual athlete, they also typically fail to outline the drawbacks of premature RTP to the team’s performance.

Let’s face it, the whole reason any of us play the game is to win. It’s what keeps us in the starting XV and our manager/coach in a job. The best athletes on the team are only useful to the manager if they’re fit. That is the root of where the saying, “the best ability is availability” comes from. Typically, the teams that keep their strongest players on the field are the teams that do well. But system-oriented players also fulfil key roles over the course of a season. Missing them can be just as big a disruption to a team’s performance.

I have a couple of examples that I like to use, of teams keeping their players on the field to maximise performance. The most commonly cited would be Leicester City’s remarkable 2016 Premier League triumph. It is well touted that that side used the fewest players and had the fewest injuries over the course of the season. Consistency is number one in any league campaign after all. Allow the team to play together frequently, get them working cohesively as a unit and leave all the other interchanging teams in your wake.

Last year, the NRL reported more ACL injuries and tendon ruptures than usual, which can likely be attributed to a rushed RTP post-COVID. This may have been born out of necessity rather than neglect, as the tournament looked to become the first team-sport competition to get back on the field, after the enforced layoff.

However, it is notable when looking at the teams that performed better, that typically their performance in the regular season table, could be correlated with how many of these injuries the team suffered. The Panthers and Eels both managed to come through the regular season with none of these injuries. They also were the two teams that shocked the pundits and performed better than usual in the competition (1st and 3rd).

https://www.instagram.com/p/CGjqE2_nTxW/?utm_source=ig_web_button_share_sheet

This is obviously a hypothetical observation rather than a concrete correlation, as injuries are unpredictable and do not give us direct information on a team’s fatigue and RTP process. However, it is notable that the team that suffered the most combined total of ACL and tendon injuries (The Knights) also had a clean-out of their Performance staff. Coincidental or maybe not?

A spike in tendon injuries after a long layoff, has also been observed in the NFL and NBA after their respective 2011 lockouts. The rush to RTP led to injury rates >3x that of the previous year. But why does this occur and how can we prevent it from happening.

First of all, it’s impossible to prevent injury. We can certainly reduce the risk, but there will always be freak accidents and collisions that occur. What we can prioritise though, is reducing the risk of soft tissue non-impact injuries. Typically, these will occur due to a spike in volume that the tissue is unable to withstand (Demand > Capacity). This may then in some cases lead to a rupture of the tissue.

An example of this is when your coach decides that you’re going to do a full training session today, along with a set of 10 sprints, both at the beginning and end of the session. The next day, half the squad are suffering from shin-splints and hamstring DOMs, that are so bad that they can barely get out of bed. How do you think they’re going to get through the next session in two days time? Do you think that the team will get a lot of benefit out of the following sessions that week?

If we are to avoid both chronic and acute soft tissue injuries, we need to employ a graded return to sport or RTP process. If we were to break this down for GAA, we need to work on the various components of the sport. So, we may then focus on a graded return to tissue-prep/plyos, running volume/high-speed running, change of direction, and contact-conditioning.

Before we get back on the field, it can be useful to prep the tissues for what’s to come. There aren’t much better ways to do that than working within a clearly-identified, graded exercise program in the gym. For the first couple of weeks, the volume should be kept fairly low, as we look to get the best bang-for-buck whilst in the gym, but not do so much that the players become fatigued.

Now, we all know the basic movements that are to be performed, with relatively high repetitions, during reintroduction to gym (Squat, Hinge, Horizontal Push, Horizontal Pull, Vertical Push, Vertical Pull, Core). However, something that is incredibly useful for team and field-sport athletes is training not just muscular tissue, but tendons as well. There are a couple of ways that we can do this, but the most commonly used are plyometrics and isometric exercises. Like all other exercises, intensity and volume must be progressed when using these techniques to achieve adaptation.

This is where most teams get it wrong. Often, they’ll start at too high a volume, at too low an intensity. Then they’ll progress the volume too quickly and to too high a total. This load will lead to fatigue within the playing group, which will lead them to become more susceptible to injury. They also will not have spent enough time running at high intensities to protect them against the scourge of hamstring injuries. What happens then is, the players that manage to make it to the match, end up blowing up when required to let the shackles off and sprint at maximal intensity. Thus, the team is left short of key players for the following rounds of championship.

The way to combat this is to start at a low-volume of relatively high-speed running, and then progress that volume per session. The running volumes should be individualised based on the player and their position. Not really rocket science and very easy to measure and manage. A favourite technique of mine for implementation within team-sports is tempo runs.

We’ve all been there. You’ve been doing fairly light fitness sessions till now. Then all of a sudden, you’re chucked in the deep end with some small-sided games. You leave the pitch feeling fine, but the next morning your groin and glutes are so sore that you can barely sit on the toilet. This is an example of “0 to 100 real quick”. Definitely not the best way to do things.

We all know change of direction is risky. That’s when a lot of injuries occur. It’s a complex task and we want to be in control of ourselves when we’re executing that skill. This is why we need to start by drilling the skill and working on our technique at low volumes, when feeling fresh. We don’t want to be fatigued and falling all over the place, as we sloppily try to evade our opponent.

Change of direction drills and games are really easy to drip-feed into the warm-up. Again, start with simple tasks and progress to more complex. Add a competitive element and the players usually love it. Progress as you would everything else and when proficiency is at a level that you’re satisfied with, let the shackles off and get after it. Then and only then is it time to start sending your players in for maximal effort games and scenario type play.

We all know that contact is a key component of any team-sport. That’s why the 40 year-old at corner-back is still playing senior after all these years. It’s easy for them to use their nous and physicality to bully the opposition’s youngsters. So like all of the other components, it would be unwise to just go straight back to full contact straight away.

Similarly to change of direction, I like to gamify contact-prep and drip-feed it into the warm-up. It adds a competitive element and gets the players engaged and enjoying themselves. A lot of GAA contact comes from a side-on hip-to-hip or shoulder-to-shoulder position. So, then in my opinion, all players can benefit from becoming more comfortable within these positions. Whether in a seated, kneeling or standing position, learning how to manipulate your opponents body-weight is quite a useful skill. Like everything I’ve already mentioned so far, it’s important that you start with the extensive variations first and then progress to more intensive afterwards.

The big question to be asked before your team returns to the pitch this summer, is if you’re in it to win it, or if you’re just happy to be taking part again. Obviously, it’s possible to do both, but if you’re serious about coming back and leaving the rivals in your wake this season, then a graded return to training isn’t just beneficial, it’s absolutely necessary. We’ve gone a long way past the days when it was just a matter of turning up on game day and performing. It’s all about your preparation now. What is going to set you apart from the competition? What are you going to do that everyone else is not?

If you’re interested in taking ownership of your RTP then I have a couple of pre-season templates available. However, if you’re really serious about coming back the fittest, fastest and most robust player that you’ve ever been, I suggest getting in touch. There’s no time like now.

“The only true test of intelligence is if you get what you want out of life.” – Naval Ravikant

So, we can see that when it comes to our training, a certain volume of work when paired with adequate recovery is positive for our development, but if that same intensity of work is mismanaged and spiked, then the same exercise intensity can be toxic to the athlete.

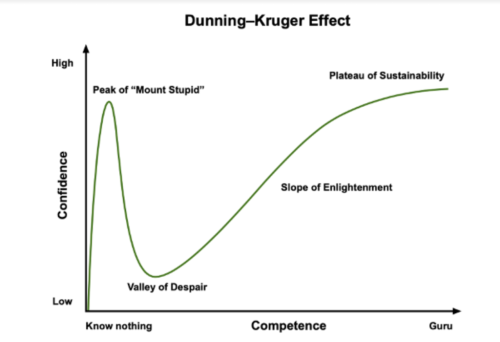

Unfortunately, it takes a fall from the peak of mount stupid, on top of the Dunning-Kruger curve, for many of these lessons to land home.

Here to help you achieve your health and performance goals.

At Petey Performance, I’ll assist you every step of the way. What’s stopping you?

Take ownership today.

© 2021 All Rights Reserved

Subscribe to Petey Performance and get updates on new posts plus more exlusive content.