Kaizen in Everything. But Why?

“The only true test of intelligence is if you get what you want out of life.” – Naval Ravikant

I’ve heard a lot of hot takes, in relation to hamstring injuries, over the past few months. It does baffle me how the same old opinions keep cropping up, but I truly believe that it’s our own fault as practitioners, as we’re obviously not educating the masses well enough. So, I thought it would be beneficial, to explain why some of these takes are a little backward and problematic, whilst also offering some solutions to a problem that presents itself time and time again.

It’s the business end of the championship season, and with the increase in pressure on the players to perform, comes an increase in pressure on their body’s to stay injury free. As always with GAA, it’s the usual suspects that crop up again and again, due to the high volumes of running load that the players get through in a week.

Hamstring injuries are by far the most common in the sport, and though they are 100% preventable, it can be a challenge to avoid running into at least a couple in the squad, due to them being so multifactorial in nature. There’s multiple coaches pulling at the players from all angles, there’s their own rest and recovery practices outside the sport and then there’s the added psychological pressure, of representing their parish against some of the county’s best players every week.

We can manage our players load as best we can, but we will never have complete control over the program, over their training loads and their lives and stressors outside of the sport. Nor should we. It’s sport after all, not life and death. No matter how badly you want to win that elusive county championship, it shouldn’t take over every aspect of your life.

Though we can do our best to have our players in the best shape possible, and physically able to tolerate the intensities and volumes of the sport, it’s near on impossible to predict exactly what workload they’re going to get through come match-day. At a sub-elite level, it’s also an educated guessing game as to whether your players are doing enough, or doing too much. And it can be a struggle to convince the other members of the coaching ticket, and the players themselves, when they’re pushing too far.

Unfortunately, our training is much like a steak. It’s pretty much impossible to undo the damage, once it’s been over-done. So, less is more most of the time. They’re much better off, getting to the game having done a little less, than getting to the game overdone and coming off with an injury after 5 mins.

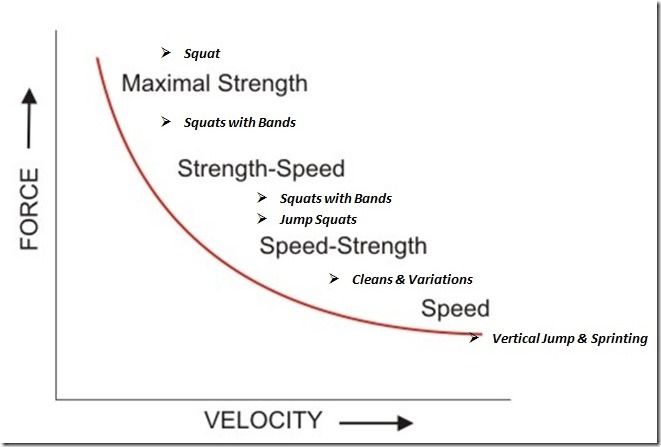

Another puzzling one for players is that, what we do in the gym does not in any way replicate what we do on the field. A lot of what we do within the four walls of the weight-room, is expose the players to exactly what they won’t get on the field of play. The movements we perform in there, are a lot slower than those on the field. So, the hamstrings might be being contracted in a variety of exercises, but they won’t be contracted as quickly as they would in a maximal sprint.

So then, why do we do them?

Well when performing a slower movement, we can improve the capacity of the muscle to produce force. The higher the amount of force we can produce, the stronger we can be. But as outlined earlier, it’s not all about strength. We must also perform exercises at the other end of the spectrum, which are more focused towards speed. This would be our med-ball work, plyometrics and powerful movements with lower resistance.

To explain this, it’s best to use the force-velocity curve below. We must train the hamstrings to be able to work effectively at all points on the curve, whilst not placing too much emphasis on any one point.

However, the best time to do this is probably in the pre-season or the off-season, as it can be difficult to perform the necessary volume-load, to develop such qualities in-season, with the added stress of repetitive competition. So, in the season, what we are focused on is getting the dosage just right, without doing too much. A fine line as well.

But what we do on the pitch, and managing our load there, is undoubtedly more important and valuable, than what we’re doing in the gym.

A huge predictor of re-injury, is the individual’s confidence to return to play. So, very simply, whether you think you can, or you think you can’t, you’re probably right. But this is where we come in as practitioners. We can help the player through their rehab and return to play process, providing metrics and milestones that they have to get through, before they return to play. As they hit these milestones, and their bodies adapts to training, so will their minds.

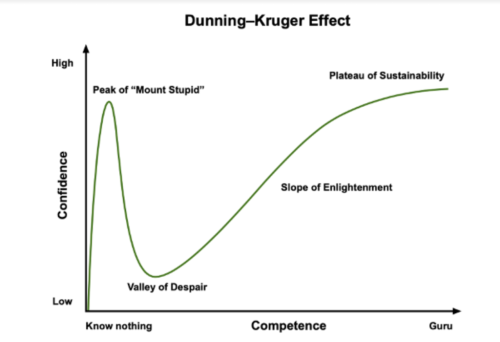

Confidence comes slowly and progressively. It doesn’t just happen overnight. By offering the athletes an opportunity and a specific goal to strive for, you provide them with the opportunity to reach new found levels of confidence when they get there.

So, the coach or physio that told you that your hamstrings are never going to be 100%, is probably right. As long as you continue working with them, with that kind of negativity and fixed-mindset, you’re probably not going to develop the necessary physical or mental capabilities to get back on the field, performing at your best.

You see the body is a dynamic and robust organism. Just because an area has been injured before, doesn’t mean that it’s completely impossible for it to ever perform better than it did previously. So, if you treat your body as such, and look to improve and get the most out of yourself, then you likely will. Sit in the corner sulking, doing clamshells with a resistance band and you’ll likely remain there.

This is the biggest bug-bear of athletes up and down the country, and it doesn’t seem to be going away any time soon. It’s a bit of a hard sell, to explain to 55 year-old Paschal, that the game that these lads play, is extremely different to the one that he played in his youth. And more over the fact, he was actually useless when he played anyway.

You see, with advancements in sport science, S&C, nutrition and the natural evolution of society as a whole, we’ve see a huge change in the ability of the athlete’s on the field of play. Now, this has led to the game becoming faster and more entertaining, as the players ability to create force, sprint and change direction quickly, as well as score points from all angles, has improved.

But the same as a car crash, with more force, comes more danger. If any athlete has the ability to run a 9 m/s, they’re probably at more risk of a serious hamstring injury, than Paschal who never got above 4, even in his prime.

The game has moved on, and with it, the demands placed on the players has increased. So, the question isn’t, “Can he get through a game?”. It is “Will he be any use to us at all, if he’s only playing at 50%?”. If the answer to that is no, and there’s more important games coming down the line, then you’re probably better off allowing the player to rest and recover, so that you can have him close to his best for the next big fixture. Rush someone back to the field of play, and you’ll likely be rushing to warm-up a substitute for him a few minutes after the throw-in.

So, in summation, give hamstring injuries their fair dues. It’s not the end of the world, unless you treat it like so. But equally if you don’t treat it with adequate respect, it’ll likely to persist for a lot longer than expected. Consult with a decent physio and S&C coach, and make sure that they keep an open dialogue with you and your GAA coaches. After all, it takes a village to raise a child.

“The only true test of intelligence is if you get what you want out of life.” – Naval Ravikant

So, we can see that when it comes to our training, a certain volume of work when paired with adequate recovery is positive for our development, but if that same intensity of work is mismanaged and spiked, then the same exercise intensity can be toxic to the athlete.

Unfortunately, it takes a fall from the peak of mount stupid, on top of the Dunning-Kruger curve, for many of these lessons to land home.

Here to help you achieve your health and performance goals.

At Petey Performance, I’ll assist you every step of the way. What’s stopping you?

Take ownership today.

© 2021 All Rights Reserved

Subscribe to Petey Performance and get updates on new posts plus more exlusive content.