Kaizen in Everything. But Why?

“The only true test of intelligence is if you get what you want out of life.” – Naval Ravikant

Agility:

(noun)

1. Ability to move quickly & easily.

2. Ability to think and understand quickly.

Change of Direction:

(verb)

When looking at the two, we can see that there is one clear difference. Agility has a double meaning, in that, it takes into account both the process of reacting to a stimulus and the action of changing direction with speed. If we look for a definition in relation to a sporting context, we may find that it is more appropriately described as “a rapid whole-body movement with change of velocity or direction in response to a stimulus” (Sheppard, 2005).

Therefore, in order to be “agile” on the field of play we must be able to react and respond effectively to the scenario that we are presented with. There is a clear tactical component to this response, as the athlete must understand the sport very well to know what the most effective response or next move should be.

It obviously helps to be able to execute a wide array of movement options. So in this way, the ability to change direction (COD) is a precursor to elite agility. Elite COD ability gives the athletes more tools in their toolbox, but they still must be able to select the right tool for the job.

Working on COD can have a positive effect on agility, by giving the athlete more tools and by refining their ability to execute certain movements efficiently and effectively. However, they still need to be able to select the correct tool for the job.

So, by breaking down various movements to their component parts and developing the athlete’s ability to execute them, we can positively influence COD ability, which will then positively impact agility. But unfortunately, working on agility by itself may not have similar effects on ability to change direction.

This is because often the stressor in the agility drill or game is too complex to allow the athlete to focus on their COD mechanics. So, it is beneficial to hold off focusing too much on agility type scenarios initially, until effective COD mechanics have been ingrained in the athletes repertoire.

When we attempt to learn a skill, we must always take into account that initially we will have to focus consciously on its execution. This takes into account theories and models from human psychology, learning theory and motor skill acquisition.

In relation to learning, there are 4 stages of competence. Unconscious incompetence, conscious incompetence, consious competence and unconscious competence. This theory outlines that before we can execute a skill without thinking about it, we must first move through stages where we must intensely focus on our actions in order to achieve the desired outcome. Initially we will be unable to execute the skill effectively despite our efforts, before progressing to a stage where we know what we should be doing, but are unable to do so consistently.

Eventually, we become competent at it’s execution, whilst we focus intently on our own actions. Through repetition we can ingrain this movement pattern and make it non-conscious. This is why it is useful to break down movements and build them back up, adding blocks as we go, getting closer and closer to the specific game scenario.

As we add components to the scenario progressively, it is useful to take into account the stages of motor learning (Fitt and Posner, 1967). This is similar in a way, as it states that initially athletes will go through a cognitive stage, where they must first seek to understand what it is that they should do.

They then move to the associative stage, where they have an idea of what they should be doing, but experiment in order to find the most consistently successful action. The athlete is still conscious of what they are doing, (similarly the 2nd & 3rd stages of the competence model) but they are forced to make adjustments, make mistakes and movements may take longer than expected.

Finally, if they are diligent enough and exposed to the right cues and environment, they will move to the autonomous stage. This is where we see elite athletes residing. They can execute the skill effectively and expertly, without needing to think about it. They become so good that if you asked them what they just did, they may struggle to explain how they did it. It becomes non-conscious and instinctive.

From this breakdown of the theory, I’m sure you can see why we should break down both sporting movements (COD) and tactical/technical movements (Agility) in order to guide the athletes to a stage of unconscious competence and an autonomous stage of execution. Unfortunately, what I typically see are drills and games on far ends of this COD-Agility spectrum.

Coaches have their athletes execute movements initially under no constraints and with no live response to a stimulus, before throwing them into a game with an active or a number of active defenders. You can see how an athlete will struggle to execute the movement effectively when there is no graded exposure to the stimulus in question. They may then throw out everything that they have just learned, as they focus solely on trying to achieve the desired outcome of the game (i.e. scoring). This is not the athletes fault, as we are all inherently competitive and have a distaste for loss or failure. Unfortunately, it seems as if we are setting the athlete up to do so by jumping a number of stages of the process.

Now I’m not bashing all coaching practices here. I do believe that we break down many of the movements well and many coaches do focus on improving movement quality. We also definitely incorporate agility focused drills and games into training. And gameplay or matchplay also has an agility component. However, the middle of the process is often missed.

What the current common practice also neglects, is the fact that between stimulus and response, there needs to be a clear process of information processing. This comes in the form of visual scanning, pattern recognition, peripheral awareness, perception of space and time and then in turn specific informational processing. Only after this has occurred, can the athlete respond effectively in the most precise way. And obviously this comes with the clear importance of prior knowledge and experience of similar situations as a crucial factor. As the above theory of the learning emphasises, graded exposure to such situations will lead to the athlete being more comfortable in the specific scenario and more able to respond with the appropriate response.

Now given that I am a S&C coach, as well as a skills coach, I may be extremely biassed, but I do believe that we should have a well thought out level of progression when it comes to all of our skills and coaching. This may be because I see tactical and technical skills in the same way that I see sporting movements. In relation to S&C, we break the sport down into its component parts and then work on them in the gym. This is called reverse engineering and it is the most effective way to both teach movement patterns and achieve transfer that will impact performance positively on game-day. So, I find it useful to do the same in relation to most skills on the field.

So, if I were to be afforded free reign in relation to how we develop young athletes’ ability to change direction, I would use the following progression, which takes into account

This is the first stage of the process and is what I spoke about earlier. Relevant movement patterns are performed in a closed environment. The athlete may be given cues to execute the movement more efficiently and effectively, but the timing of execution is up to them. Through repetition, we can hopefully teach efficient movement technique & ingrain the most effective pattern for that athlete.

After we’re happy with the athlete’s level of proficiency, or the athlete becomes bored with the completely closed environment, we can progress the complexity of the drill and increase the intensity, by giving the athlete a stimulus to respond to. This stimulus can be auditory, visual or both.

Auditory stimuli can come in the form of a whistle or a call from a coach or athlete, so the athletes are now learning to react and respond quickly and complete a task.

However, as alluded to earlier, the athletes will not often be required on the field to perform an agility action in relation to an auditory stimulus, so we can progress to a more sport-specific scenario by adding in a visual cue to react to. This may be in relation to a cone or light, or to make it more specific again, it may be in relation to the movements of another athlete or opponent.

However, at this stage of the process we are still focused on general movement patterns, so the scenario that the athletes work in will be a closed one.

We may place a constraint on the athlete, meaning that they must perform a specific movement action or task, such as a lateral shuffle, sidestep, crossover step or deceleration. This is so that we progress the complexity and the intensity of the specific movement in question.

As we progress along the General to Specific spectrum, we must break down relevant game-specific scenarios into their most basic parts. This involves developing skills in a 1-on-1 scenario, but first it can be advantageous to reduce the intensity and take out the competitive element to allow the athletes to execute the movement effectively. However, we now need to add in a more specific cue. In order to replicate what opponents will do, but allow our athletes to focus on their own movements, it can be useful to add in passive defenders into the scenario.

These defenders will perform similar movements to those of in-game defenders, but will telegraph those movements, so that the attackers know where they are going and how to respond to their movement.

This affords our athletes an opportunity to get used to responding to a specific defensive manoeuvre, whilst also focusing on executing the necessary movement expertly. In this way we are now at the “Pattern Recognition” stage of the process. The athlete uses visual scanning, peripheral and spatial awareness and knowledge of the situation to execute the desired response effectively.

Through repeated exposure to this stimulus, and by progressing intensity, we can hopefully lead to lower reaction time in this specific scenario on the field. We may also afford the athlete more time to focus on the execution of the necessary movement, but this time under specific time pressure.

As we continue to move towards a more open environment, we can now start to “gamify” our drills. This means that there is now a clear competitive element to the movement, with both attacker and defender being given a task to complete, in order to determine success or failure. It’s amazing what this will do to the intensity of your drills! Watch how much buy-in you achieve to the process.

However, given that we are still focused on developing movement skills for one specific action, it can be useful to add in constraints to the game in order to favour one side. If we are focused on attacking agility actions, then we may just give those athlete a head start on the defenders, by adjusting position, timing or space. We may also use a “unequal” scoring system, to favour one team and make another more averse to failure. (eg. Attacking win = 2 points, Defensive win = prevent a point) Likewise, if we want to favour the defensive agility action, we can do the same in the opposite way.

As the athletes become more proficient at pattern recognition, movement execution and response, we can now equal the playing field and step back as a coach. We can devise training drills and games in a 1 vs 1 context, that replicate specific scenarios the athletes will find themselves in during a match. Now the real competition begins and I’ve found it useful to group athletes together into teams during this part of the process. Keep the score and watch as the competitive nature of your athletes comes out. This is a perfect scenario as it can motivate athletes who are more individualistic and intrinsically motivated, as well as those that enjoy working as part of a team.

Now my skills coaching hat comes off and my tactical coaching hat goes on. We now can incorporate more elements of team-play in similar environments, with larger space and more chaos added, in terms of additional players. Athletes must now react and respond to both their opponents and their teammates. Communication becomes an even more important part of this stage of the process and it is an incredibly useful time to work on specific scenarios that the team is struggling with. This is where a ball becomes a more essential piece of kit, to make the scenario relevant to the game.

Again, we can favour one team or side (attacking vs defending) over the other, by adding in constraints and/or unequal scoring measures. We can use uneven team numbers (2 v 1, 3 v 2, 5 v 3, etc.) in order to favour one side. And we can place the emphasis on either attack or defence depending on the focus of the day’s training. This is the stage of the process that most closely resembles current training practices in rugby union, rugby league and soccer, but from what I see, is not used as much in Gaelic Games yet. Obviously this is where the S&C coach and skills coach are most likely to dip out, and hand over care to the tactical coaches.

Now we’ve progressed up to the part of training that most resembles the actual on-pitch sport demands. The athletes probably don’t have much time to focus solely on agility actions, as there is so much other information to process. And opportunities will be limited to do so, but we can still favour one team over the other, by adding in unequal team-numbers and/or specific constraints on attack or defence to give more space to one side. We can also create more opportunities to work on specific scenarios, by giving points or turnovers for specific actions (eg. tackled in a certain area = turnover, score in a certain way or player beaten in a certain area = additional points)

Now, we’re at the final stage of the process. Let the athletes go out onto the field and put into practice all that they’ve learned. Sit back and relinquish all of your control. If you’ve done all that you can on the training field, then you should be able to let the athletes work it out for themselves on match-day. It takes a lot of self-control and confidence to allow your athletes to go out and play with complete freedom. Sure, they’ll make mistakes, but these are the mistakes that they’ll learn the most from. Let them do so, review, plan and go again.

Only by being willing to sit back and let them have control are you truly empowering them. You teach them the skills but they are the ones that must put them into practice. They are the ones that need to be making the decisions on the field. They are the ones that need to be comfortable trying things and making mistakes.

Athlete-empowerment.

That’s what being a coach is all about.

“The only true test of intelligence is if you get what you want out of life.” – Naval Ravikant

So, we can see that when it comes to our training, a certain volume of work when paired with adequate recovery is positive for our development, but if that same intensity of work is mismanaged and spiked, then the same exercise intensity can be toxic to the athlete.

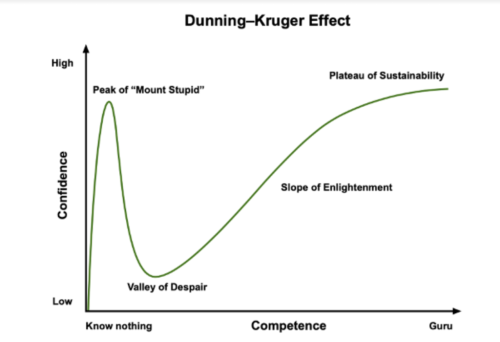

Unfortunately, it takes a fall from the peak of mount stupid, on top of the Dunning-Kruger curve, for many of these lessons to land home.

Here to help you achieve your health and performance goals.

At Petey Performance, I’ll assist you every step of the way. What’s stopping you?

Take ownership today.

© 2021 All Rights Reserved

Subscribe to Petey Performance and get updates on new posts plus more exlusive content.