Kaizen in Everything. But Why?

“The only true test of intelligence is if you get what you want out of life.” – Naval Ravikant

All outstanding teams have one quality which they perform better than anyone else. A distinctive style that is in line with their cultural identity as a team. For the All Blacks, it’s transitioning from defence to attack. For the Springboks, it’s winning the physical battle. For France, it’s playing what they see in front of them (Joué joué as they say). And for Ireland, it was for years, keeping a hold of the ball and depriving the opposition of time and space.

Now, when you hear rugby S&C, what springs to mind are images of the world’s best athletes shifting tin in the gym. However, this is such a small proponent of an effective S&C program, that the narrative has got to be changed. Sure, we can look to develop our athletes within the weight-room, but everything we do in there is to support what we do on the field.

See, pretty much everything we do in the gym is general, when directly applied to the sport. Yes, we may perform exercises with a high degree of specificity. But a high degree of specificity to a given movement. This movement will be one of many that will be performed on the field of play. So then, in relation to sport performance, it can be classified as general work. The only truly specific exercises that we perform in relation to the game, are the drills and games in training that replicate or exceed game demands. So, our actual rugby training.

Now, when people think about rugby training, they think the S&C coach’s job is over. The book stops here and the S&C steps away, relinquishing care to the sport coach. However, I’m afraid performance and training exist across a spectrum, so it’s not quite as black and white as that.

Sure, the S&C coach will not typically offer technical or tactical advice. That most definitely is the rugby coach’s job. But, the physical demands of gameplay are still largely the S&C coach’s baby. That is why the S&C coach should be used as a consultant throughout the training process.

The games and drills that are used in training, should be used specifically. That is to say, that they’re programmed with a specific goal in mind.

That might be that we want to improve our tackle technique and execution. So then we may look to create and control the contacts within our games that we play. How does that apply to the S&C coach? Well we might have to ask the S&C coach, “how many contact scenarios will we experience in a game?” and “what would the density of those tackle situations be?”.

That basically means, how many tackles will a player typically have to complete in a game, at what intensity and over how much time? How many tackles can our players then execute in a given amount of time without seriously increasing their risk of injury? We may then look to use this information in our training drills/games to make them more appropriate to in-game demands, or even slightly higher than in-game demands at certain stages of the season.

Maybe we want to improve our transitions from defence to attack. So then, we will manipulate the game scenario to lead to more turnovers. We then may place constraints on the counter-attacking side that lead to them having to make use of the ball quickly, with rewards for high-quality execution. But how does that apply to the S&C coach? Well how many turnovers are in a game? How many of these efforts can be repeated without fatigue playing a part and having a significant effect on execution? And how long should the efforts be before taking a break? How much ground will a player typically cover during these efforts? Are the players covering these distances during these games? Or do we need to do some additional conditioning work as a top up to our small-sided games?

If we have a particularly big side that is great in the contact-area, but weak at getting around the field, then we may use our small-sided games to improve the quality of our contact-area play, but also stress the players in terms of their running demands. This could be as simple as making the field bigger or taking out players to create more space, whilst still keeping an element of controlled contact play throughout. Potentially we may always start off play with a ruck or maul, so that they still get that stimulus, before they are forced to run a significant distance at high speed once the ball is shipped out.

But we also need to be there and willing to pull the plug when they have done enough. There’s no point in completing heaps of volume at lower speeds, when that won’t happen in a game. Keep it short and snappy. How long is the ball typically in play in a game? What’s the worst case scenario? Let’s work back from that.

These are just a few examples but I hope you get the idea. If teams have a S&C coach on hand on-pitch, their knowledge and experience should absolutely be used throughout the session. That doesn’t mean they have to be in control of everything. All they need do is present the coaches with the information in a digestible manner. After that, it’s up to the sport coaches to decide whether they want to use it or not.

This is why communication and interpersonal skills are such an important part of the job. Knowing how to present relevant information to each coach, in a language that they understand and are able to then use, is an undervalued skill. For a long time, the S&C coach has been seen as the nerdy, weights-obsessed, recluse that lives inside the gym. Now we are starting to see that the more they are involved in the coaching team and the decisions that are made, the greater the impact that they can have.

Talk to other coaches. You just might learn something.

“The only true test of intelligence is if you get what you want out of life.” – Naval Ravikant

So, we can see that when it comes to our training, a certain volume of work when paired with adequate recovery is positive for our development, but if that same intensity of work is mismanaged and spiked, then the same exercise intensity can be toxic to the athlete.

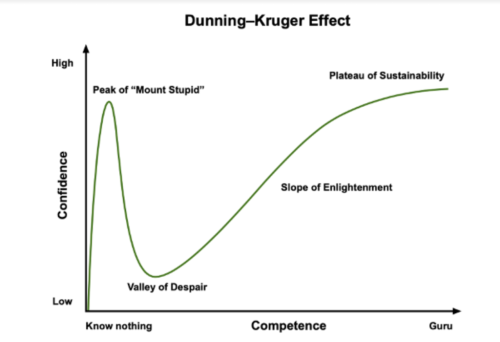

Unfortunately, it takes a fall from the peak of mount stupid, on top of the Dunning-Kruger curve, for many of these lessons to land home.

Here to help you achieve your health and performance goals.

At Petey Performance, I’ll assist you every step of the way. What’s stopping you?

Take ownership today.

© 2021 All Rights Reserved

Subscribe to Petey Performance and get updates on new posts plus more exlusive content.