Kaizen in Everything. But Why?

“The only true test of intelligence is if you get what you want out of life.” – Naval Ravikant

S&C Coaches run into the same problem all the time when working in a team environment. Given that they have limited resources and time, they choose to prescribe the exact same training program to every athlete in the group regardless of their age, physical function, experience or playing position.

Now in some cases, where there hasn’t been a culture of elite-level S&C and performance previously, this approach may work well. In such an environment the lowest hanging fruit is actually getting the athletes to participate in some form of physical preparation consistently.

Until your athletes are all showing up and giving their best efforts on a regular basis, there is probably little point in attempting to individualise the training approach. A comprehensive and well-adhered to general approach to physical preparation will trump a well thought out but poorly implemented specific approach every day of the week.

However, once you have buy-in to your program, athletes have developed a solid foundation in their GPP and have had a few years of experience in training consistently, it may be necessary to make things a little bit more specific to break through plateaus and continue to develop physically.

What got the athletes to this point, will likely not get them much further. You can only squeeze so much juice out of an orange.

In order to achieve different adaptations, we will need to expose our athletes to different modalities of training. That may mean different volumes and intensities, different exercise variations or different means of training completely.

This is why when programming across a season, we often move along a general-to-specific continuum. It is why during the pre-season, we move from a period of general physical preparation (GPP) to a phase of specific physical preparation (SPP) and then finally a phase focused on specific development (SD) of the athlete’s physical ability for their given sport.

In team-sports, it may be difficult to identify points in the season where you’ll overreach the athletes, before backing off and allowing them to recover and realise their newly-developed physical qualities. As a result of the intense fixture schedule, a linear approach to periodisation won’t work. However, that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try to have our athletes peak at certain periods throughout the year, for the most important games and competitions.

A vertical integration approach to periodisation is likely the best model for team-sport athletes in this arduous environment. This means we focus on developing all qualities at once, but place the emphasis on certain ones at different stages of the season.

Should the emphasis be placed on similar qualities for every athlete in the squad?

Probably not.

Athletes are different people. They have different requirements and will respond differently to the same training stimulus. This is why an individualised approach is necessary for the development of every athlete in the group. However, given that we have limited time and resources, it is fairly obvious that we can’t write 30 completely different programs. And nor do we need to.

In order to make it easier to cater for the different needs within a specific group, it can be beneficial to split your athletes into groups based on their needs. Categorising your athletes is the easiest way to do this and below I have a simple framework which I’ve used with success in the past. It is based on the common archetypes that I’ve come across whilst coaching in team-sports through the years.

From my experience, team-sport athletes typically can fall into 3 categories.

These categories of athletes obviously need very different things in their training, so we must alter the training stimulus for each group.

How you identify which athletes go into each group is up to you. It is possible to eyeball your athletes and simply observe who you believe should be in each group. Yet it is likely more advantageous to do some type of testing in order to categorise the groups.

Assessing strength and reactivity can obviously be done by using maximal strength tests and jump tests. However, I don’t believe it suitable or necessary to use the old school 3RM tests with a group of GAA athletes. If you’re already using a Countermovement Jump/Squat Jump and/or a Drop Jump/10-5 Hop test to monitor and assess readiness of your athletes, then I believe you can use those same tests to assess which group they should be in.

If the ratio of their strength lies on the side of better force generation capabilities (SJ or CMJ) and less reactivity (lower DJ or 10-5), then they obviously need more stiffness and elasticity. If they lie on the opposite end of the ratio, then they likely need more of a strength stimulus.

Anecdotally, what I commonly see is that younger athletes test well in terms of reactivity, but lower in terms of force generation capability. Whilst, older athletes typically test better in terms of slower strength measures, but are often less reactive. A lot of this may be put down to the discrepancy between their training ages within the gym. With the older athletes having been exposed to almost a decade or more of strength work, and the younger athletes having less than 4-5 years of structured strength & conditioning.

As a result, we can say that in general, older athletes will fall into category 1 above. Whereas younger athletes will fall into category 2. Category 3 will then be made up of the athletes that have had enough exposure to strength training to meet the requirements and standards of elite-level athletes in the sport, as well as being reactive enough that they are within the ranges for athletes of their age in the sport.

So once you’ve categorised your athletes, what’s next with the programming for each group?

You’ll be thankful to hear that the spine of the program will remain similar, with athletes completing the same movement patterns but with varied volume and exercise variations. As I’ve said before, I’m not going to get hung up on which bilateral or unilateral squat pattern an athlete selects, as long as they bring intent to the lift and execute it with a high level of proficiency. If someone doesn’t want to complete a back squat, but is comfortable executing a trap-bar deadlift, then I’m not likely to throw the toys out of the pram.

Likewise, if someone slept poorly last night, is experiencing a high level of emotional stress at home or at work, or is feeling under-recovered from their last session, I don’t really mind what specific volume they get through. It is going to be better for them to complete 3 high-quality sets at a higher intensity, than it is for them to complete 5-6 sets of lower quality, lower intensity and lower intent.

Giving your athletes these options in relation to their session selection will have the added benefit of giving them more autonomy in their program, which will likely lead to improved buy-in as a result of their feelings of freedom. However, even with this added variability to the program, it is clear that each of the groups still need to have a different emphasis in relation to which physical qualities are most important.

So, group 1 (strong but less reactive athletes), will typically have a lower volume of strength training prescribed, with more extensive plyo variations and isometric holds to bolster the elasticity of their tendons. We can likely sub out some of the compound movements and sets, in favour of more extensive means of training that will develop the qualities that are most important for them, in order to keep them on the field and performing near their peak. As this group is typically the oldest in age and often have the poorest recoverability, the volume that is prescribed to them is likely the lowest of the 3 groups. It is probably closer to the minimal viable program that you have in your head. You do as much as is necessary, not as much as possible.

Group 2 (less strong but more reactive athletes), are typically on the younger end of the group and have the lowest training age as well. They can typically recover a little but faster, and likely have a higher work capacity, so you can be a little bit more aggressive with them in relation to their volume-load and the amount of lifts they will get through in order to develop both their muscular strength and size. Reps are what they have been missing up to this point, so it’s fine to prescribe more reps if you want to optimise their development for the years to come. You’ll be surprised how robust and resilient young athletes can be, so don’t be afraid to stress the system significantly to elicit the desired adaptation.

Then with the third group of 3, they are already pretty strong and pretty reactive. However, in my experience, when working with GAA athletes, they typically have had a decent level of exposure to a heavy emphasis on the development of maximal strength and hypertrophy in the past. So, with this group, I tend to steer the program in the direction of development of maximal speed, rate of force development, change of direction ability and robustness of common injury sites. This will form the main template for your program anyway so my advice is to get this down on paper first, before you edit the program slightly as needed for the other 2 groups.

If we then look at speed development then we may break athletes down into categories again.

However, I think that’s a topic for another day.

So, if you’re working with a team of athletes and struggling to figure out how to individualise the sessions, give the above a go and see how you get on.

Then, off the back of that, if you’re an athlete that has reached a plateau and has been let down with a general approach to your S&C, then make sure to identify what your needs are and don’t be afraid to get in touch.

A general approach will only work for so long.

Once we’ve got the most out of that, then it may be time to change some things up to go even further.

“The only true test of intelligence is if you get what you want out of life.” – Naval Ravikant

So, we can see that when it comes to our training, a certain volume of work when paired with adequate recovery is positive for our development, but if that same intensity of work is mismanaged and spiked, then the same exercise intensity can be toxic to the athlete.

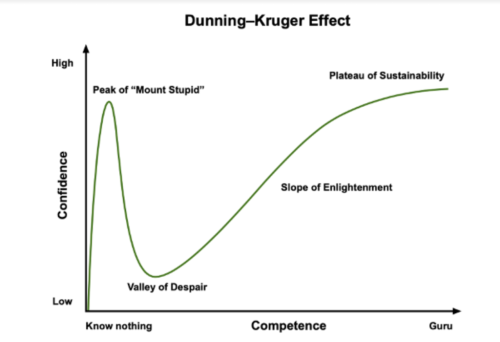

Unfortunately, it takes a fall from the peak of mount stupid, on top of the Dunning-Kruger curve, for many of these lessons to land home.

Here to help you achieve your health and performance goals.

At Petey Performance, I’ll assist you every step of the way. What’s stopping you?

Take ownership today.

© 2021 All Rights Reserved

Subscribe to Petey Performance and get updates on new posts plus more exlusive content.