Kaizen in Everything. But Why?

“The only true test of intelligence is if you get what you want out of life.” – Naval Ravikant

When you become injured, there is a sheer sense of shock, loss, grief & restlessness. This is normal. For many athletes, their identity as a player and as an athlete is a huge aspect of their personal identity. When the opportunity to showcase their athletic talent and to compete is taken away from them, they lose a huge aspect of who they are as a person. They no longer can do the thing that they love doing the most in the world and as a result there is a sense of loss and a sheer lack of purpose that accompanies that experience.

In the moments, days, weeks and months post injury, it is incredibly important that they are shown that they are cared about, that they feel understood, valued and feel as though there are people around them that will help them to get back to their best. It is important that they are shown that they still hold value as a person and relationships with coaches, athletes and peers are continued as best as possible, as if these are cut off, it can lead to an overwhelming feelings of lack of self-worth and confusion.

If the athlete is a part of a team, then they have lost a huge opportunity for connection in their life. This can lead to feelings of isolation and loneliness, so it is important to check-in on them regularly, continue to involve them in the team environment and set aside new opportunities for connection and conversation outside of the sport.

Our thoughts impact our emotions and our emotions impact our behaviours and habits. If we are to become the athlete that we want to be, we know that it is incredibly important that we practice a high performance mindset. We do this in order to reduce feelings of stress, practice a growth mindset when it comes to achieving tasks and overcoming challenges and to remain consistent even in the face of adversity. There is no adversity greater to our identity as an athlete than succumbing to a serious injury that takes away our ability to compete. So, in order to get back to where we once were and to even surpass it, we must take care of our mental health and our mental performance.

Another clear knock-on effect of poor mental health and performance is chronic feelings of stress and anxiety. These can impact negatively on our physical health over time by leading to a suboptimal balance of stress hormones which can have a negative affect on our recovery time. So, in a way mindfulness and mental health techniques are absolutely key during the rehabilitation process if we wish to recover as best and as quickly as possible.

I have went through this experience myself in the past, experiencing clinical depression at the same time as chronic hip and groin pain, as well as at a later stage experiencing a relapse of depression whilst undergoing my own recovery from an ACL reconstruction. Both of these rehabs were long and arduous and from my experience were certainly not helped by my mental ill-health at both times. When it’s difficult to get out of bed in the morning, difficult to eat meals at all and even face the social interaction at the gym or in your physio session, it’s definitely not going to lead to high quality preparation and training. Poor sleep, poor fuelling and poor and inconsistent training may follow, which in conjunction with low mood, suboptimal circulation of stress hormones and feelings of hopelessness can lead to an increase in symptoms of pain, which further exacerbate the issue.

This is something that I’ve noticed with my athletes and myself over time working through long RTP processes.

Those that recover more quickly are typically those that remain most positive in their rehabilitation and chances of recovery. They enter the gym or club-gate with positive feelings around their capabilities of facing this challenge head-on and overcoming it. As a result, they don’t let failure get to them. When they fail, they learn, they get up and they try again.

Our language as coaches is also incredibly powerful and can have a huge influence over our athletes beliefs around their fragility or anti-fragility. Focus on the negative and you may make them feel as though they are getting everything wrong. Focus on the positive and you may help them to see that they are getting a lot right! Focus on fear of movement and the risks involved and you may well influence them to be afraid of even giving it a go. Focus on improvements and how far they’ve come and they may very well be able to see that they are capable of helping their body to adapt and as a result there is no reason why they can’t get back to their best!

You are their guide, so you may as well be a positive and helpful one!

If an athlete comes to me and they can’t see things getting any better, can’t see their issue being improved in the future and can’t envision a future in which they’re moving pain free and functional, then it is unlikely that they will ever get there.

If they don’t believe they can get better, then they don’t trust me or my process. If they don’t trust me or my process, then it’s unlikely that they’ll bring intent and consistency to the rehabilitation process. If they don’t do that, then it’s obvious that the chances that they will be able to overcome the issue and return to the pitch pain-free are reduced.

All squats are not born equal. All hinges are not the same. How you run loads different tissues differently. How you sprint, cut and jump loads each of your limbs in a different way. If we accept this, then we can accept that rehab and RTP is not simply a case of prescribing exercises and ticking the boxes beside them when they’ve been done. How you perform an exercise, including the strategy, the intent, the tempo and the feeling you’re chasing, are all incredibly important. And these aspects of training are even more important in rehabilitation and RTP when a certain tissue has been loaded to the point of injury. So, therefore it must be loaded again in order to achieve an adaptation and following that process, integrated into a new, more efficient movement pattern to reduce the risk of it happening again.

Feedback is an incredibly important tool in the training process. It gives us information in regards to the efficacy of what we’ve just attempted to do. Have we been successful in what we’ve set out to achieve? Should we continue doing what we’re doing? Should we change what we are doing slightly? Or should we throw it out altogether and try something else?

When you are going it alone, you lack the external feedback necessary to remove the ego from the equation. Having a coach or therapist to make unemotional decisions is quite obviously a bit of a cheat code in the training process. However, even coaches and therapists can be slightly biassed in their beliefs and actions. Therefore if the practitioner you’re working with has access to external tools or perspectives elsewhere, they too will be getting a more balanced view of where you are and where you’re going. Objective data and consultations with other experts are thus incredibly valuable to you both, so then they should be sought out, rather than blocked out.

I used to believe that there was some sort of formula out there for the solution of just about any specific injury. I thought that you could write a system so robust and so detailed that it would be capable of solving any issue, no matter the context. This was useful in that I was able to systemise my own specific process for addressing particular injury sites and get it down in paper. I was able to write general guidelines for progression through its stages and I was able to fall back to this system when my head was fried with doubts and stress. However, what I’ve discovered through the years of trial and error is….

Yes, there are KPIs that we should aim to hit if we are to be more likely to be successful in certain rehab cases.

But…

There is no one-size-fits-all approach that works with every single case

There are anomalies, there are outliers, there are nuances.

Each program must be catered to the individual in front of you. And each individual in front of you has different circumstances, different beliefs, different anthropometrics, different asymmetries, different physical capacities and different needs

Take your system. Take what works for them. Put it in the program. Take what doesn’t work for them. And take it out.

Write the program with the athlete in mind.

Fit your model around them. Don’t expect them to fit neatly into your model.

I have helped 100s of athletes through the trials and tribulations of athletic careers plagued by injury, and one thing I can say for certain is, it is never over. I’ve worked with so many athletes who believed their best days were behind them. And with the vast majority, we’ve been able to get them back to a level where they weren’t just meeting their prior levels, bit surpassing them.

Sure, it’s terrible to be sidelined and unable to play the game, to compete and train alongside your teammates. But, it sure is a good opportunity to iron out the kinks that you’ve been putting off ironing out. To focus on your weaknesses in terms of both physical energy leaks and skill development. If you choose to see that you now have an opportunity to not just get from game to game, an opportunity to not just go about your business week by week until the end of the season and an opportunity to get the extras in that so many others are not, then you very well may be capable of making the most of this precious time.

When you’re juggling many balls at once, trying to improve every single aspect of your abilities as an athlete, it can be easy to become a jack of all trades and a master of none. If all you’re focused on doing is keeping the plates spinning, then I would say that you’re likely doing the exact same thing that you do during the season. You’re focusing on so many things at once, that it will be very unlikely that any will improve.

Pick your big rocks. These are the things that will really push you forward as an athlete at this stage of the process. Prioritise these above all else. These are the need-to-haves. Don’t ignore these in favour of the nice-to-haves.

I’ve made this mistake myself as a coach. I’ve attempted to fit so many things into a session that each individual tool is diluted in its effectiveness. It takes real confidence to say “I believe that this is an important aspect of your movement that will help you to get back on your feet and this is what we’re going after today.” It also takes real confidence as an athlete to say “I trust your judgement and I will apply myself as best as I can in this session to get the most out of it.”

If you are successful in implementing one component of the process, then for sure build on it, but don’t go adding too many ingredients to the mixture all at once.

If you were baking a cake then you might add flour, eggs, sugar, butter and milk to the mixture.

The cake tastes pretty good.

The next time you make a cake you add flour, eggs, sugar, butter, milk and cocoa powder to the mixture.

The cake tastes bad. So, you can make the assumption that the cocoa powder was the part of the mixture that spoiled the process.

However, if you added flour, eggs, sugar, butter, milk, cocoa powder, vanilla extract, buttercream, baking soda, sprinkles, raisins, orange zest and chocolate chips to the mixture, then it would be pretty difficult to identify where you went wrong.

There are aspects of our preparation that set us up to be more effective thereafter. Like preparing for an interview, studying for a test, prepping a kitchen counter for a meal or setting out our tools for some DIY, our preparation will increase the chances of success as well as the ease at which we can find success in the subsequent session. There are aspects of our preparation for rehab or return to play sessions that I’m sure we would rather not do. However, if we want to get the most out of the work that we do, it would be wise to set ourselves up for success. Don’t go through the motions and just execute as a means to an end. Focus on what you are doing, bring intent to each action and you will reap the rewards down the line.

Often if athletes have come to me and say that they feel they’re not getting transfer of their drills to their performance or they’re not making any progress, then this is where I look first. Often this is the very place that we make the most easy gains. I mean, if you’re going to do it anyway, you may as well do it well.

Injury occurs when capacity and tolerance does not meet the demand. Chronic injury happens when this very principle occurs consistently over time. However, during the training process, we push our bodies with progressively increasing demands to stimulate adaptation. What plays a crucial role in this adaptation process? Recovery of course.

Training + Recovery = Adaptation.

So therefore, it’s not just a matter of turning up and getting the training in. It’s about what you do in the other 23 hours of the day that has a huge bearing on whether you’ll recover over time. Do the right things. Eat well, sleep well, hydrate and reduce stress. Otherwise, you’re simply pissing into the wind.

Only by moving more into the RTP space, did I fully realise just how much of an absence of both information and progressive practice there is in this area. Sometimes we have a tendency to look at the industry through rose-tinted glasses. Because we surround ourselves with peers who continually seek to learn, grow and improve, we think everybody in the industry does that. Through recent weeks working with various athletes, not only have I realised that the vast majority are not interested in improving, but they also are far more interested in demonising and tearing down those that are.

The good news is, there is a definite need to attempt to fill this gap and seek to guide athletes through this stage of the process, and it’s also very easy to stand out from others in the industry.

Seek out knowledge, try new things, have conversations, don’t be afraid to be wrong, be a kind, adaptable and understanding person and you most certainly will be able to have a positive effect on the industry at large.

To springboard off my previous point, it is very likely that you do not know it all as a coach or practitioner. As a result, it is likely that you and your athletes would benefit from an external perspective and opinion of someone that may potentially not be from the exact same background or area as you. If you have vast knowledge in the late-stage of the return to play process, then you may benefit from the counselance of someone with more experience in the early stages. Don’t be afraid to have these conversations. Don’t be afraid that someone will tell you how to do your job. If you’re worried about these conversations I’d say it implies that you…

If you’re an athlete reading this, then seek out those practitioners that are comfortable opening a dialogue with others. From my experience, the best ones often are.

Injury rehabilitation is not a linear process. There will be peaks and troughs. And it will certainly seem as though there are more troughs than peaks. Knowing that there will be more adversity and obstacles will help you to prepare for them. Looking at your previous experience of overcoming these obstacles will improve your perceived coping skills and ability to get through them. If we know that these obstacles are coming and that we are capable of getting through them then it will help us to have greater patience when we do face them. Remember, patience is not the action of waiting. It is how we act while we are waiting.

Often when pundits or analysts speak about players that have overcome many injuries in their career, they will refer to them as resilient. This is obviously a quality that is highly sought after in sport. However, resilience is not something we are born with. It is something that we hone through practice. Therefore we can’t build resilience without facing adversity. So, therefore this injury is not only an opportunity to improve our resilience, but it is the only way we can do so.

This resilience doesn’t just come from returning to play after the initial injury has been suffered. It comes through overcoming the small obstacles day by day and sticking with the process when things aren’t going well. It comes from not becoming disillusioned when things don’t happen as quickly as you’d like them to, not throwing the toys out of the pram when more obstacles are thrown in your way and not rushing through the process because of external circumstances or expectations. Run your own race. Take it one small step at a time. No task is too small. No obstacle is too great.

Denial is a real aspect of the trauma response to injury. However, it’s most certainly not going to lead to any growth or any greater chances that you’ll get back on the field in a better position.

Until an athlete acknowledges where they are, what they’re currently capable of and what they’re not capable of, it is unlikely that they will be able to ascend up the return to performance ladder. If you are to work on what’s important, then you’ve got to identify what is important at this stage of the process and not skip past it in favour of other, more glamorous alternatives. This requires acceptance and an ability to be present. Nothing happens until both of these are achieved.

Injury is an isolating experience and rehabilitation is a selfish one. In order to set priorities and place certain tasks and behaviours at the top of the staircase, then you’ve got to place others below them. Some tasks and environments will not serve your overall goal of getting back to full fitness. As a result, they may have to be sidelined and that may mean less opportunities for connection with the people that you execute those tasks with. If someone does not serve you in your pursuit of the overall goal, then perhaps that person will have to play a lesser role in your life at this time. If that person cannot or will not understand and appreciate these selfish (or self-focused) actions that you must do, then maybe they don’t want to be in your life as the person you are now. They want you to be the person that they want you to be. This is likely an unhealthy level of expectation and as a result maybe it’s time that you move on from this particular relationship. Especially if there’s a mismatch between the person you want to be and the person that they want you to be.

The rehabilitation process is a hard one. It can be a long one. And it is most definitely a period of time where you will experience a lot of physical, mental and emotional growth as a person. It’s quite possible that through the process of transforming your athleticism, you simultaneously transform as a person as well. Whilst this might not necessarily be a bad thing, it’s important to recognise it and be aware that it is ok for this to happen.

Through all of the rehabilitations that I’ve been through, all the late night conversations, the lonely rehab sessions, the tough conversations, the arguments and the tears, I can safely say that it has never not been worth it.

That feeling of getting back out and playing, the feeling of succeeding, of your dreams coming into reality and of getting back doing what you love. It trumps the challenges twentyfold.

So when you’re questioning why you even bother, why you are stuck in this stupid gym, why you have been dealt this hand and if it would be better if you just gave up, let me say with confidence, that your future self will thank you for staying in it.

Stay in the hunt. Take it day by day. Complete the small, menial tasks. Be as diligent as you can. And there absolutely is light at the end of the tunnel.

A hell of a lot of it.

“The only true test of intelligence is if you get what you want out of life.” – Naval Ravikant

So, we can see that when it comes to our training, a certain volume of work when paired with adequate recovery is positive for our development, but if that same intensity of work is mismanaged and spiked, then the same exercise intensity can be toxic to the athlete.

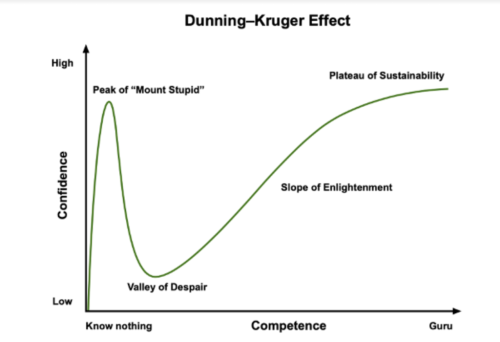

Unfortunately, it takes a fall from the peak of mount stupid, on top of the Dunning-Kruger curve, for many of these lessons to land home.

Here to help you achieve your health and performance goals.

At Petey Performance, I’ll assist you every step of the way. What’s stopping you?

Take ownership today.

© 2021 All Rights Reserved

Subscribe to Petey Performance and get updates on new posts plus more exlusive content.